On the occasion of Amsterdam Gallery Weekend, Fernando Sánchez Castillo is presenting Liberty for All: a work produced as an edition, a small wooden version of the Statue of Liberty, but now with the face of a non-white person. The Statue of Liberty was a gift from France to the United States, a gesture of friendship in honor of the centennial of the Declaration of Independence. It was ultimately dedicated on 28 October 1886. Inspiration for the Statue of Liberty came from Édouard René de Laboulaye, a prominent political thinker and outspoken advocate of the abolition of slavery. It is said that the original plan of erecting the statue dates back to a conversation between De Laboulaye and the French sculptor Fréderic Bartholdi. With the statue they wished to pay tribute to the Afro-American soldiers, emancipated from slavery, who fought in the American Civil War; for that reason they proposed to model the statue after a portrait of an Afro-American person. That idea proved to be a bridge too far however. Not until 2017 would the face of a non-white Lady Liberty appear on an American coin.

The Statue of Liberty is a monument that symbolizes freedom. Sánchez Castillo’s small wooden version of it has an ambiguous title. ‘Liberty for All’ refers, in fact, to all movements of protest and emancipation that are aimed at achieving equal rights and freedom for all. At the same time the title betrays the hope that this statue, and especially its inherent meaning, will reach as many as possible. The fact that the statue is being produced as an edition, and that the work is available for a modest price, is meant to underscore that wish.

Another work in Sánchez Castillo’s exhibition Retro-Expectatives is a mental map, a collection of diverse objects brought together in an installation. Sánchez Castillo’s mental map is a representation of the history of the Statue of Liberty, based on a study of (hidden) information and the subjective interpretation of this.

‘Lady Liberty’ is an iconic monument. Monuments and iconic images from mass media make up a recurrent motif throughout the work of Fernando Sánchez Castillo. His artistic strategy focuses on the idea of transformation and what images gain and lose in the manipulation of reality, facts, depictions, memories. In the transformation a new narrative is made visible. The work of Sánchez Castillo reveals his command of scale, material and process; and he links those formal elements to his knowledge of, and insight on, history and the effects of power on people and social structures.

A key theme throughout the exhibition is the continually dialectic relationship between freedom and justice: contemporary art’s struggle to reconcile the social tensions that arise in this constant battle. Here the ‘angel of history’ theory – a melancholy view of history as an endless cycle of despair – which Walter Benjamin described in 1940, in response to the drawing Angelus Novus by Paul Klee, is being applied as a way of alleviating pain caused by the concept of ‘progress’ and the deployment of power.

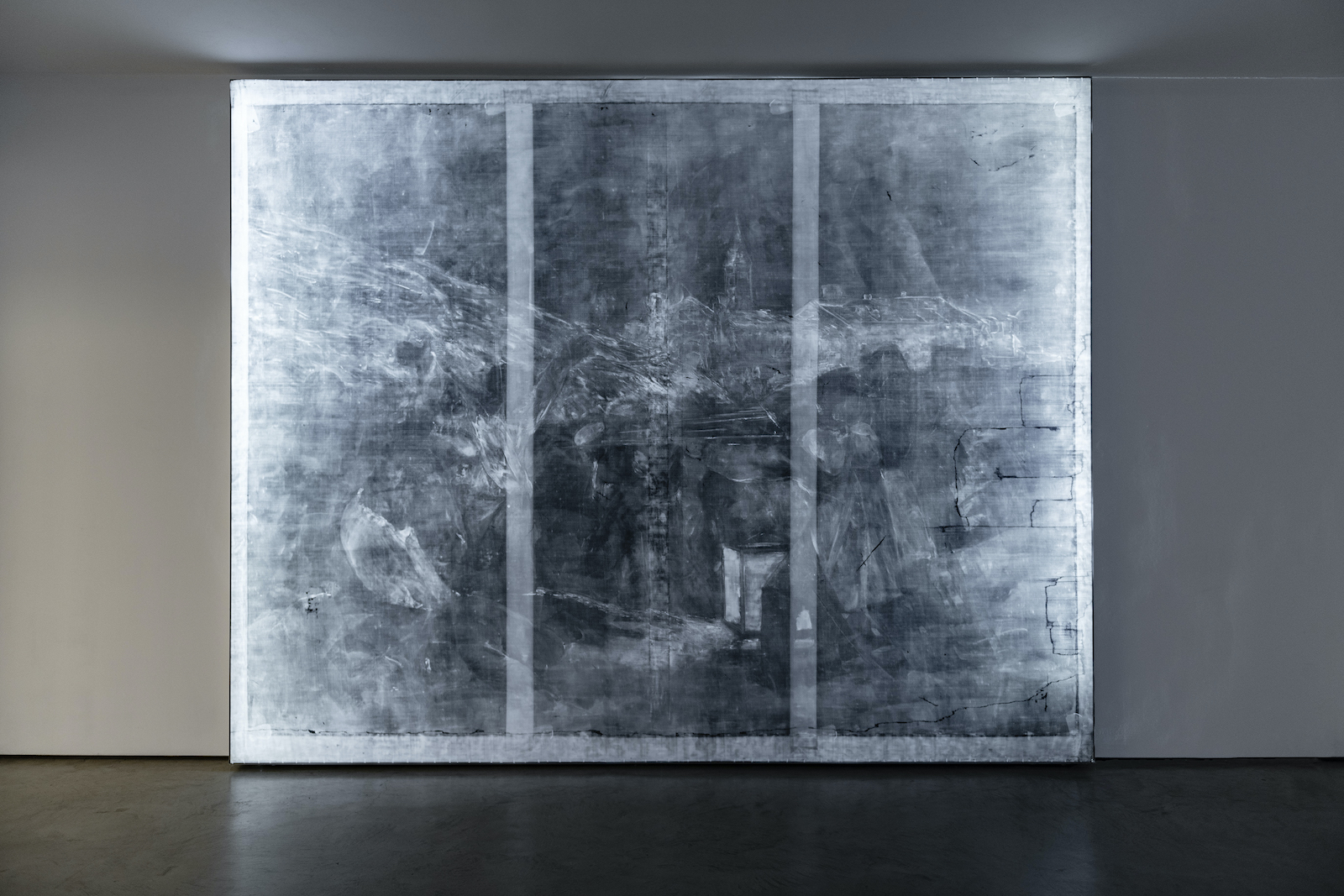

The work Hechos del 2 de mayo (Facts of 2 de Mayo), 2015, portrays the tension between freedom and justice in an incisive manner. Sánchez Castillo made a lightbox containing an x-ray exposure of Goya’s famous painting El 2 de mayo 1808 en Madrid, o ‘la lucha con los Mamelucos’ (The second of May 1808 in Madrid, or ‘The Fight against the Mamelukes’), which has the same measurements as the original. The image shows traces of damage done in 1939 as a result of bombardments during the Spanish Civil War. Conservation work carried out on the painting in 2008 restored it to its original condition, thereby causing the damage to vanish from view. Sánchez Castillo: “One of the most important anti-war paintings in history was damaged during our Civil War. (…) Now we can see that gap, that has been restored (…) as an abstract injection of reality into the painter’s composition.”

In his work Sánchez Castillo contemplates the ways in which art can contribute to the undermining of icons, such as the Statue of Liberty or the paintings of Goya, in order to recharge them with new meanings. The exhibition is an ode to the power of the anonymous and constructive protest, as well as an attempt to ‘reset’ collective memory. Retro-Expectatives invites us to think of history as fiction, as a construct in which expectations and desires lead the way, and one which must be revised time and again.